Byzantine Mosaics

Mosaics were more central to Byzantine culture than to that of Western Europe. Byzantine Orthodox church interiors were generally covered with golden mosaics. Mosaic art flourished in the Byzantine Empire from the 6th to the 15th centuries. The majority of Byzantine mosaics were destroyed during wars and conquests, but the surviving remains still form a fine collection.

The Orthodox churches of Emperor Justinian like the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, the Nea Church in Jerusalem, and the rebuilt Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem were certainly decorated with early Christian mosaics but none of these survived. Important fragments survived from the mosaic floor of the Great Palace of Constantinople which was commissioned during Justinian's reign. The figures depicted, including animals & plants, are all classical but they are scattered before a plain background. The portrait of a moustached man, probably a Gothic chieftain, is considered the most important surviving mosaic of the Justinianian age. The so-called small sekreton of the palace was built during Justin II's reign around 565-577. Some of the fragments of Byzantine period mosaics of this vaulted room still survive. The vine scroll motifs are very similar to those in the Santa Constanza and they closely follow the Classical tradition. Also, there are remains of floral decoration in the Orthodox Church of the Acheiropoietos in Thessaloniki (5th-6th centuries).

In the 6th century, Ravenna, the capital of Byzantine Italy, became the center of mosaic-making. Istria also boasts some important examples from this Byzantine cultural era. The Euphrasian Basilica in Parentium was built in the middle of the 6th century and decorated with mosaics depicting the Theotokos flanked by angels and saints. Fragments remain from the mosaics of the Church of Santa Maria Formosa in Pola. These pieces were made during the 6th century by artists from Constantinople. Their pure Byzantine style is different from contemporary Ravennate mosaics.

Very few early Christian Byzantine mosaics survived the Iconoclastic destruction of the 8th century. Among the rare examples are the 6th-century Christ in majesty (or Ezekiel's Vision) mosaic in the apse of the Osios David Church in Thessaloniki which was hidden behind mortar during those dangerous times. The mosaics of the Hagios Demetrios Church, which were made between 634 and 730, also escaped destruction. Unusually, almost all of these Byzantine art mosaics represent Saint Demetrius of Thessaloniki, often with his suppliants before him.

In the Iconoclastic era, figural mosaics were also condemned as idolatry. The Iconoclastic churches were decorated with plain gold mosaics with only one great cross in the apse like the Hagia Irene in Constantinople (after 740). There were similar crosses in the apses of the Hagia Sophia Church in Thessaloniki and in the Church of the Dormition in Nicaea. After the victory of the Iconodules (787-797 and in 8th-9th centuries respectively, the Dormition church was totally destroyed in 1922), these crosses were substituted with the image of the Theotokos in both churches. Similar mosaics depicting Theotokos flanked by two archangels were made for the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople in 867. The dedication inscription says: "The images which the impostors had cast down here pious emperors have again set up." In the 870s the so-called large sekreton of the Great Palace of Constantinople was decorated with the images of the four great iconodule patriarchs.

The post-Iconoclastic era was the heyday of Byzantine art because of the most beautiful mosaics executed. The mosaics of the Macedonian Renaissance (867-1056) carefully mingled traditionalism with innovation. Constantinopolitan mosaics of this age followed the decoration scheme first used in Emperor Basil I's Nea Ekklesia. Not only was this prototype totally destroyed later, but each surviving composition is battered, making it necessary to move from church to church to reconstruct the system. An interesting set of Macedonian-era mosaics make up the decoration of the Hosios Loukas Monastery. In the narthex there is a depiction of the Crucifixion, the Pantokrator, and the Anastasis above the doors. In the church, there are mosaic depictions of the Theotokos (apse), Pentecost, scenes from Christ's life, and hermit St. Loukas (all executed before 1048). These scenes were made with minimum detail and the panels are dominated with gold setting.

The Nea Moni Monastery on Chios was established by Constantine Monomachos in 1043-1056. The exceptional mosaic decoration of the dome, showing the nine orders of the angels, was destroyed in 1822, but other panels survived (figures depicted were Theotokos with raised hands, four evangelists with seraphim, scenes from Christ's life, and an interesting Anastasis where King Salomon bears resemblance to Constantine Monomachos). In comparison with Osios Loukas, the Nea Moni mosaics contain more figures, details, landscape and setting.

Another great undertaking by Constantine Monomachos was the restoration of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem between 1042 and 1048. Nothing survived of the mosaics which covered the walls and the dome of the edifice. The Russian abbot Daniel, who visited Jerusalem in 1106-1107 left a description: "Lively mosaics of the holy prophets are under the ceiling, over the tribune. The altar is surmounted by a mosaic image of Christ. In the main altar one can see the mosaic of the Exhaltation of Adam. In the apse the Ascension of Christ. The Annunciation occupies the two pillars next to the altar."[6]

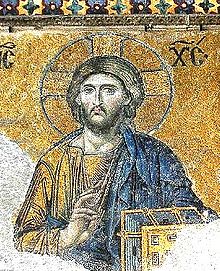

The Daphni Monastery houses the best preserved complex of mosaics from the early Komnenian period (ca. 1100). The austere and hieratic manner typical of the Macedonian epoch, was represented by the awesome Christ Pantocrator image inside the dome, which was metamorphosing into a more intimate and delicate style. A superb example of this is The Angel before St Joachim, with its pastoral backdrop, harmonious gestures, and pensive lyricism. The 9th- and 10th-century mosaics of the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople are truly classical Byzantine artworks. The north and south tympana beneath the dome was decorated with figures depicting prophets, saints and patriarchs. Above the principal door from the narthex we can see an Emperor kneeling before Christ (late 9th or early 10th century). Above the door from the southwest vestibule to the narthex, another mosaic shows the Theotokos with Justinian and Constantine in which Justinian I is shown offering the model of the church to Mary while Constantine is holding a model of the city in his hand. Both emperors are beardless - this is an example of conscious archaization as contemporary Byzantine rulers were bearded. A mosaic panel on the gallery shows Christ with Constantine Monomachos and Empress Zoe (1042–1055) in which the emperor gives a bulging money sack to Christ as a donation for the church.

The dome of the Hagia Sophia Church in Thessaloniki is decorated with an Ascension mosaic (c. 885). The composition resembles the great baptistries in Ravenna, with apostles standing between palms and Christ in the middle. The scheme is somewhat unusual since the standard post-Iconoclastic formula for domes used to only contain the image of the Pantokrator.

There are very few existing mosaics from the Komnenian period but these must have survived by accident and give a misleading impression. The only surviving 12th-century mosaic work in Constantinople is a panel in Hagia Sophia depicting Emperor John II and Empress Eirene with the Theotokos (1122–34). The empress, with her long braided hair and rosy cheeks, is especially capturing. It must be a lifelike portrayal because Eirene was really a redhead (her original Hungarian name was Piroska). The adjacent portrait of Emperor Alexios I Komnenos on a pier (from 1122) is similarly personal.

The imperial mausoleum of the Komnenos dynasty, the Pantokrator Monastery, was decorated with great mosaics but these were later destroyed. The lack of Komnenian mosaics outside the capital is even more apparent. There is only a "Communion of the Apostles" in the apse of the cathedral of Serres. A striking technical innovation of the Komnenian period was the production of very precious, miniature mosaic icons. In these icons the small tesserae (with sides of 1 mm or less) were set on wax or resin on a wooden panel. These products of extraordinary craftmanship were intended for private devotion. The Louvre Transfiguration from the late 12th century is a fine example of this. The miniature mosaic of Christ in the Museo Nazionale at Florence illustrates a more gentle & humanistic conception of Christ which began to appear in the 12th century.

The sack of Constantinople in 1204 caused the decline of mosaic art for the next five decades. After the reconquest of the city by Michael VIII Palaiologos in 1261, the Hagia Sophia was restored and a beautiful new Deesis was made on the south gallery. This huge mosaic panel, with figures that were two and a half times that of lifesize, is really overwhelming due to its grand scale and superior craftsmanship. The Hagia Sophia Deesis is probably the most famous Byzantine mosaic in Constantinople.

The Pammakaristos Monastery was restored by Michael Glabas, an imperial official, in the late 13th century. Only the mosaic decoration of the small burial chapel (parekklesion) of Glabas survived. This domed chapel was built by his widow, Martha around 1304-08. In the miniature dome the traditional Pantokrator can be seen with twelve prophets beneath. Unusually, the apse is decorated with a Deesis, probably due to the funerary function of the chapel.

The Church of the Holy Apostles in Thessaloniki was built in 1310-14. Although some vandal systematically removed the gold tesserae of the background, it can be seen that the Pantokrator and the prophets in the dome follow the traditional Byzantine pattern. Many of its details are similar to the Pammakaristos mosaics so it is assumed that the same team of mosaicists worked in both buildings. Another building with a related mosaic decoration is the Theotokos Paregoritissa Church in Arta. The church was established by the Despot of Epirus in 1294-96. In the dome, the traditional stern Pantokrator is depicted, with prophets and cherubim below.

The greatest mosaic work of the Palaeologan renaissance in art is the decoration of the Chora Church in Constantinople. Although only three panels of the mosaics of the naos have survived, the decoration of the exonarthex and the esonarthex constitutes the most important full-scale mosaic cycle in Constantinople right after the Hagia Sophia. These were executed around 1320 by the command of Theodore Metochites. The esonarthex has two fluted domes, especially created to provide the ideal setting for mosaic depictions of the ancestors of Christ. The southern one is called the Dome of the Pantokrator while the northern one is the Dome of the Theotokos. The most important panel of the esonarthex depicts Theodore Metochites wearing a huge turban, and offering the model of the church to Christ. The walls of both narthexes are decorated with mosaic cycles from the life of the Virgin and the life of Christ. These panels show the influence of the Italian trecento on Byzantine art demonstrated by the more natural settings, landscapes, & figures.

The last Byzantine mosaic work was created for the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople in the middle of the 14th century. The great eastern arch of the cathedral collapsed in 1346, bringing down the third of the main dome. By 1355, the big Pantokrator image was restored and new mosaics were set on the eastern arch depicting the Theotokos, the Baptist, and Emperor John V Palaiologos (discovered in 1989). In addition to the large-scale monuments, several miniature mosaic icons of outstanding quality were produced for the Palaiologos court and nobles. The loveliest examples from the 14th century are Annunciation in the Victoria and Albert Museum and a mosaic diptych in the Cathedral Treasury of Florence representing the Twelve Feasts of the Church.

During the troubled years of the 15th century, the weakened Byzantine empire could not afford luxurious mosaics. Consequently, churches were decorated with wall paintings, and especially after the Turkish conquest.